intro

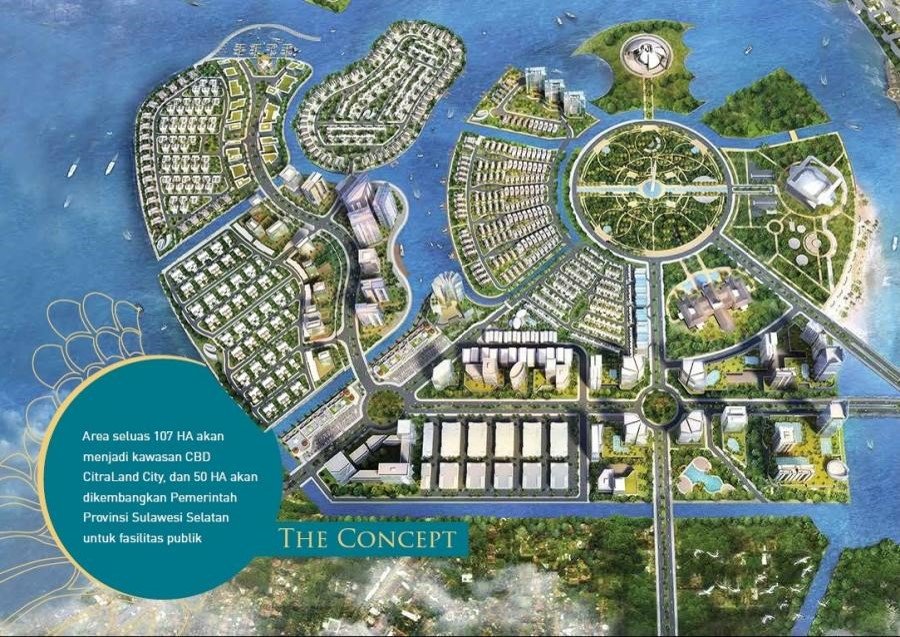

It sounds like a golden opportunity: Dutch companies working together with the Indonesian government to create new land near the coastline of metropolis Makassar in South Sulawesi. On the spot where a small island already exists, five new artificial islands will be created in the shape of a Garuda (eagle), the national symbol of Indonesia. With this new land, named Centre Point, more space is created for housing, business, public facility and green space for the growing population of Makassar. However, there is a considerable catch to this story.

The Netherlands

The Indonesian government appoints the Centre Point project to KSO Ciputra Yasmin, which outsources the land reclamation to the Dutch company Boskalis. Their bid wins the contract of 75 million euros to construct the artificial islands in 2017. It is subsequently up to Atradius Dutch State Business (DSB) to identify the risks involved in this project and report back to the Dutch Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Finance.

The Centre Point project is classified by Atradius DSB as a Category A project (high risk) because of the size of the land reclamation and the possible negative consequences for the environment and the living circumstances of the people. After a year of extensive research into the social and environmental consequences, Atradius DSB issues a positive recommendation to the Dutch government to insure this transaction, which is what the government does. And so Boskalis starts the job, but not without concern.

80% less fish due to erosion of the coastline

The coastline of Makassar has three natural barriers that protect the land from the sea. The first is coral reef, followed by seagrass and finally sand. In order to build the artificial islands, a significant amount of this sand was removed, severely damaging one of the barriers and leaving several fishing villages to deal with the consequences according to research done by the Indonesian environmental organization WAHLI South Sulawesi and the Dutch human rights and environmental organization Both ENDS.

Not only did the fish population and thus the fishermen’s income decrease by 80%, but 21 houses were heavily affected by the increased erosion of the coastline. Also, in two fishing villages parts of the cemetery have been washed away and disappeared into sea. The villagers have only managed to save a few bodies of their buried ancestors, the others were simply lost.

Forced eviction

In order to create five new islands off the coast of Makassar, 43 families living on the already existing island were forced to leave their homes. They were neither heard nor compensated. In 2014 they were simply taken away by the police. Since then some of them live under a bridge in the open air, are crammed up in a small room with a whole family or live illegally on public domain. But most of them have disappeared, address unknown, since the forced eviction.

Hope for the future

Despite all of this, the local community does not want compensation for their suffering. Now that the work is done and the fish population is finally starting to recover, they would like to look ahead and focus on the future. What they do want, however, is recognition.

The local community should have played an important role in this story. They should have been heard and their worries should have been considered. By getting this acknowledged, they hope to prevent equal suffering by other local communities from similar projects in the future. That is why they filed a formal complaint against Atradius DSB together with WAHLI South Sulawesi and Both ENDS.

Complaint against Atradius DSB

The complaint mainly consists out of the fact that Atradius DSB should have checked whether there had been any consultation with the local population about the possible consequences of the Centre Point project. In this case that did not happen properly. “We don’t object to the fact that foreign companies come to Indonesia to do business and earn money, but it has to be done fair and just,” Amien from WAHLI South Sulawesi explains. “We would like to see a fundamental change, in which businesses are not only having an eye for profit, but also for the environment and the impact on the local community.”

“When I first got involved in this case, I was very angry with the Netherlands. I wanted compensation for the livelihood of the local fishermen and for everything that they lost. But that is the practical side of the matter on the short term. I realized that it’s more important to look at the long term and to ensure that governments and companies become aware of human rights, the environment and the specific impact of these projects on women. We need to learn from what happened in Makassar.”

Therefore, WAHLI South Sulawesi has been collecting information on this case for years. Together with Both ENDS and the local community they have processed this information into a formal complaint of 140 pages, for which they have revisited the affected locations.

Hearing the local community

“The complaint is about two things,” Niels Hazekamp from Both ENDS explains. “First of all, Atradius DSB has not properly defined the project and has not checked whether all the stakeholders had indeed been heard about the potential risks of this project. Atradius DSB never spoke directly with the fishing communities even though there was compelling reason to do so. It would have given them many valuable insights that did not come to light until the complaint was filed.”

Who is responsible?

“Second of all, the complaint is about responsibility. Atradius DSB is linked to the negative impact of the Centre Point project through Boskalis. They have not recognized that yet. In fact, they state that it is not (yet) proven that the negative consequences such as the dramatic decrease of fish and the erosion of the coastline are due to the activities of Boskalis for the Centre Point project. With this complaint we hope to come to a joint recognition of the responsibility of Atradius DSB.”

WAHLI South Sulawesi and Both ENDS have been to Atradius DSB to discuss the complaint. “It was a good talk in which we got the feeling that people were listening,” says Niels. “We would now like to see Atradius DSB reach out to the local fishermen near Makassar.”

Whether this actually is going to happen, is yet unclear. But the conversation certainly gives hope for the future, setting a precedent to hear the local community about the potential risks of similar new projects. And that is exactly what Amien of WAHLI South Sulawesi had in mind: that we take note and learn from what went wrong in Makassar, so that we can prevent this from happening again in the future.

Atradius DSB is currently analyzing the complaint in detail.